Of the original Seven Wonders of the Ancient World—the Great Pyramid of Giza, the Colossus of Rhodes, the Lighthouse of Alexandria, the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, the Temple of Artemis, the Statue of Zeus at Olympia, and the Hanging Gardens of Babylon—only the Pyramid of Giza remains standing. The rest have been damaged or destroyed by the passage of time, calling attention to the impermanence of cultural artifacts.

Today, threats such as iconoclastic acts, overcrowding from tourism, conflicts, natural calamities, flawed restorations, and commercial misuse continue to jeopardize the survival of significant artistic and cultural treasures. But at Wake Forest University and worldwide, researchers are using technology to preserve history against further decay. Photogrammetry—the creation of 3D models using 2D photographic images—3-D scanning, panoramic photography, and more enable the generation of meticulous digital records and creation of highly detailed replicas. Combined with blockchain, an encrypted digital ledger, researchers can both document, help establish provenance for artifacts, and pursue repatriation for looted items. And Wake Forest students from multiple disciplines are getting the opportunity to engage in this groundbreaking work.

In June of 2022, a story in Wake Forest Magazine traced the fascinating history of a wooden dish from Fiji acquired by Capt. James Cook in the 1770s. This dish ended up at the Lam Museum of Anthropology at Wake Forest. The story explains how a chance meeting between then Provost Rogan Kersh and Susan de Menil (P 19), a design consultant and cultural heritage thinker, led to the development of an innovative, interdisciplinary collaboration. This collaboration aimed at using blockchain technology to track treasures of antiquity and address how to share ownership of cultural artifacts with often complex histories across disparate cultures and vast expanses of time, particularly when the repatriation of these objects needs to be considered.

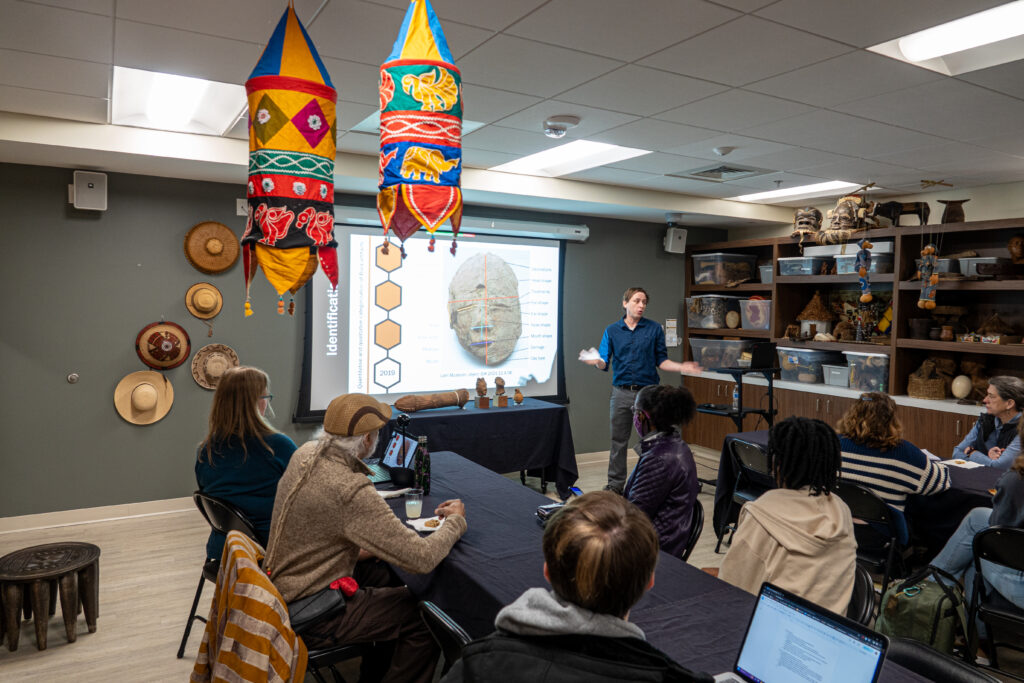

With support from the Office of the Provost and the vision and guidance of DeMenil’s Art & Antiquities Blockchain Consortium (AABC), this initiative has continued to grow and evolve under the leadership of Dr. Andrew Gurstelle at the Lam Museum. In late January, over the course of two days, Wake Forest students from multiple disciplines—including Art, Anthropology, Engineering, Art History, Law, Business, and African Studies–had the chance to take part in an experiential learning opportunity, allowing them to delve into complex issues of repatriation and cultural heritage.

The two-day event, sponsored by the Wake Forest University Interdisciplinary Arts Center, Wake the Arts and the AABC, centered around the visit of Dr. Ferdinand Saumarez Smith, director of Factum Foundation’s London office and leading voice on the use of technology in cultural preservation. Debates about ownership and repatriation of cultural property are often presented as a zero-sum-game. But with the advent of digital technologies for recording and replicating surfaces, such as 3D scanning and printing and CNC-milling, attitudes about replicas, authenticity, and repatriation are changing, and students were eager to learn more about Factum’s work and its implications.

Dr. Gurstelle set the stage on the first day with an informal lunch and learn lecture. Using his research as a backdrop, he introduced his audience to the concept of provenance and repatriation of cultural artifacts. Provenance, which has particular value in helping authenticate objects, is the chronology of the ownership, custody, or location of a historical object. Essentially, it’s a matter of documentation. Tracing the provenance of an object or entity is typically a means of providing contextual and circumstantial evidence for its original production or discovery, by establishing, as far as practicable, its history, sequences of its formal ownership, custody, and places of storage, but it’s often a challenging undertaking.

In addition to the aforementioned Fiji dish, the Lam Museum is also home to a collection of terracotta sculptures. Donated by a collector of African art, Gurstelle has worked to trace their provenance. Through formal analysis, he identified the terracottas as originating from the Bura archaeological sites (ca. 3rd-11th centuries) in Niger that were extensively looted following an exhibit in the 1990s.

Cultural heritage, provenance, and repatriation are regular topics with students at the Museum of Anthropology, and Gurstelle is a strong advocate for repatriation.

“My impulse, my idea, and I think the correct one, is to move towards repatriation, returning these objects to Niger so that they can be with the larger more provenanced corpus. The center and locus of research also shifts back to local archaeologists and communities that can have some authority over the research.”

But Gurstelle also acknowledges the challenges of repatriating valuable historical artifacts to a country like Niger which is in the midst of a coup and has no recognized civilian government. Fortunately, the blockchain work that began in 2019 presents an opportunity.

“There are a number of strategies that could be employed. But the idea is that we use photogrammetry to create 3-D models– to create digital information about the shape and form of these very objects, with the belief that their shape and form is what gives them value. People want these because that’s what they look like. Their very form, their physical presence, is indicative of the people that created them 1000s of years ago. So by encoding their form, we can have a snapshot, right, a great key that directly links into this one specific object. That shape information is digital. And it can be encoded on a blockchain, on a distributed ledger. Imagining like a cloud-based system, essentially, of where there’s not a single file in one single server somewhere, but rather information that is continually passed back and forth between all of these nodes in the blockchain so that it’s distributive, it’s transparent, it’s accessible. With the idea being that it’s a receipt. If we give this back to Niger, there is now a known receipt, a new link in that provenance chain that says Niger is the owner. The government right, the people themselves. If these objects were stolen again, they could appeal to that key–this immutable, unchangeable blockchain code that contains the very shape of the object itself, providing–maybe–a durable way of demonstrating ownership and provenance.”

Nevertheless, Gurstelle is partnering with a team of experts, including Saumarez Smith and the Factum Foundation, to document the history, recover and catalog artifacts, and prepare for repatriation back to the artifacts’ place of origin.

The Factum Foundation specializes in digitally preserving important works of art and culture. One technique they use is photogrammetry. Photogrammetry involves taking hundreds of overlapping photographs of an object from many different angles and processing them using specialized software. The digital 3D model can then be used for study or outputted as a physical object via 3D printing or CNC milling.

A key focus of Saumarez Smith’s visit was using photogrammetry to build 3D models of the Bura terracottas in preparation for repatriation. Those 3D models will be combined with blockchain codes enabling future authentication by providing an unalterable record of the movement of the objects. Students from across disciplines at Wake Forest had the opportunity to participate in the scanning and learn more about the digital replication process while also thinking through the ethics, legal frameworks, and contracts for repatriation.

To conclude his visit, Saumarez Smith gave a public lecture that explored the issues of preservation and repatriation through his work on preservation of the Bakor monoliths, unique carved basalt and limestone sculptures made between the 15th-17th centuries in southeast Nigeria, as well as the Bura heads from the Lam Museum’s collection.

In order to demonstrate what’s possible with Factum’s technology, Saumarez Smith began by passing around a 3D replica of a Canaletto painting, The Campo San Salvador, encouraging participants to feel the brushstrokes of the clouds and to angle the canvas in different positions to observe the texture. He explained the detailed process of replicating the painting which ultimately results in a facsimile that, when seen at a normal viewing distance, and with the correct context, becomes indistinguishable from the original.

Dr. Saumarez Smith then turned to his work with Bakor monoliths. He first set the stage with the history of the monoliths and went on to discuss how digital technologies have been used to document and preserve the monoliths which average 6-7 ft tall and weigh approximately 220 lbs. Over the course of three trips from 2016 to 2019, he and his team documented around 300 monoliths in 30 different sites using basic photography and numbering, as well as geolocating, drone surveying, and 3d scanning the monoliths using photogrammetry. The project ventured into identifying looted monoliths housed in international museums such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Musée du Quai Branly, and the Chrysler Museum. In a significant move towards restitution, facsimiles of the monoliths were returned to their original communities by the Metropolitan and Quai Branly museums in 2022, and the Chrysler Museum, in 2023, repatriated its actual monolith to its originating community and received a facsimile produced by Factum in collaboration with the National Commission for Museums and Monuments.

Beyond the research and experiential learning opportunities for Wake Forest students, why is this project such an important one? Artifacts like the Bakor monoliths and Bura terracottas hold significant value as they represent the culture and history of the land they derive from. Gurstelle and Saumarez Smith agree that it is a moral imperative to return stolen and looted artifacts to their country of origin. But at the same time, they must be protected and their provenance safeguarded.

The collaborative partnerships and interdisciplinary nature of this ongoing project not only underscores Wake Forest’s commitment to academic excellence and innovation, but it’s also a powerful testament to how the University lives out its motto, Pro Humanitate, by fostering a community of inquiry that respects and preserves the narratives of cultures around the globe.

Through initiatives such as this one, the University continues to inspire its community to explore, inquire, and contribute meaningfully to the world’s collective knowledge and heritage.

To learn more about the Factum Foundation’s work, visit their website.